|

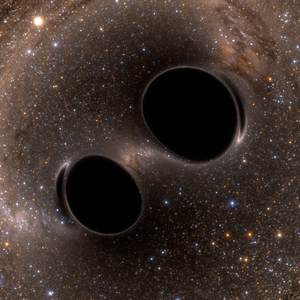

| Image Source: Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) |

Topics: Astrophysics, Black Holes, Gravitational Waves, Einstein, General Relativity, Theoretical Physics

Before now, the strongest evidence of gravitational waves came indirectly from observations of superdense, spinning neutron stars called pulsars. In 1974 Joseph Taylor, Jr., and Russell Hulse discovered a pulsar circling a neutron star, and later observations showed that the pulsar’s orbit was shrinking. Scientists concluded that the pulsar must be losing energy in the form of gravitational waves—a discovery that won Taylor and Hulse the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics. Ever since this clue, astronomers have been hoping to detect the waves themselves. “I've certainly been looking forward to this event for a long time,” Taylor says. “There is a long history, and I think projects that take this long to bear fruit require an awful lot of patience. It's about time.”

The discovery is not just proof of gravitational waves, but the strongest confirmation yet for the existence of black holes. “We think black holes exist out there. We have very strong evidence they do but we don’t have direct evidence,” Lehner says. “Everything is indirect. Given that black holes themselves cannot give any signal other than gravitational waves, this is the most direct way to prove that a black hole exists.”

Scientific American: Gravitational Waves Discovered from Colliding Black Holes

Clara Moskowitz

Comments