From humble beginnings in a series of accidental discoveries, SQUIDs have invaded and enhanced many areas of science and medicine, thanks, in part, to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

SQUIDs—short for superconducting quantum interference devices—are the world's most sensitive magnetometers and powerful signal amplifiers, with broad applications ranging from medicine and mining to cosmology and materials analysis.

Physicists from around the world celebrated last week* to mark the 50th anniversary of the first journal paper introducing the SQUID, published in February 1964.

Celebrants heard about the use of SQUIDS to measure brain activity in Finland, discover mineral deposits leading to a large silver mine in Australia, and detect faint light from the early moments of the universe from telescopes all over the world.

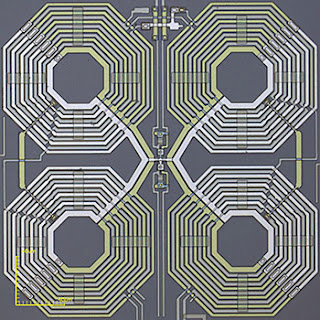

SQUIDs measure magnetic fields based on quantum properties created when a superconducting circuit loop, in which electricity flows without resistance, is interrupted with one or two short sections of resistive material. The current across the resistive section varies predictably, based on the strength of the external magnetic field, making the device an exquisitely sensitive detector of magnetic fields. Typically, SQUIDs need to be cooled to cryogenic temperatures below 4 kelvins (-269 degrees Celsius) with liquid helium.

The SQUID was invented at Ford Scientific Laboratories in the 1960s but was further developed at NIST (then called the National Bureau of Standards). James Zimmerman co-invented one type of SQUID (the RF-SQUID) and coined the term while at Ford, before joining NIST where he worked in the 1970s and 1980s.

NIST: Magnetic Attraction: Physicists Pay Homage to the SQUID at 50

Comments