Featured Posts (3520)

|

| Image Source: Science Alert |

Topics: Astrophysics, Photonics, SETI, Solar Sail, Space Exploration

Physics arXiv: Fast Radio Bursts from Extragalactic Light Sails

Manasvi Lingam, Abraham Loeb

#P4TC:

Light Sails Leakage, September 9, 2015

|

| The NASA Pi Day Challenge is an illustrated math problem set that gets students solving some of the same problems NASA scientists and engineers must solve to explore space. |

Topics: Education, Einstein, Humor, Mathematics, NASA, STEM

| Math Symbol | Pronounce Like |

|---|---|

|

| Researchers have created the world's first time crystal, an exotic state of matter that combines the rigidity of an ordinary crystal with a regular rhythm in time. (Credit: E. Edwards/JQI) |

The Flying Bullet Graphic Novel

Six years in the making. I made this sci-fi adventure for all of us. It's time we put our money where our mouth is.

Hollywood and major publishing companies won't tell our story so WE have to. Once we tell our story then we have to

support each other. START NOW. and ENJOY

Check out our new web series MESSIAH WARS. It centers around a group of young individuals with spiritual gifts that have to band together to fight the forces of evil. We merge our love of sci fi, fantasy, afro futurism and spirituality in this show!! Check it out and don't forget to subscribe!!

Episode 3

|

| Image Source: Famous Scientists |

|

| The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission during its May 18, 2016 hearing on diversity in the tech industry. (Photo: Mike Snider, USA TODAY), Link below |

Excerpt from Murder on the Eros Star

A short story from the Escape 2 Earth series

When Da’Quan entered the room Jada was sitting up in the bed, she took one look at Da’Quan and covered her eyes. Okay, she said, this is really embarrassing. Jada was a proud Lazonian female who never liked to ask for help. She moved her hand away from her face and asked, “aren’t you supposed to be at the Festival of Life on Lazon?” Da’Quan walked over to the bed and held her hand, “there’s always next year. Jada, who did this to you?” Jada looked across the room at Brazoll; she told Da’Quan how Brazoll works behind the bar to earn extra credits when he is not working his main job on the ship’s security force.

“One evening while I waited for Brazoll to complete his shift we overheard two passengers talking about a time machine. One of them said that he was to meet someone here on the Eros Star to acquire the main component to power a time ship. Brazoll thought that it was pure

fantasy; he said that the passenger reeked of the drug Obvious.” Jada was still in pain; she adjusted herself in the bed, turned to Da’Quan and continued her story. “It was clear to me that he was on something, he probably just left one of the private dens on the bottom deck of the ship, anyway I remembered the story you told me a long time ago about a Guild of Time Traveler Historians.” Jada nodded, hoping that it would somehow jog his memory; “you know the clandestine group of Lazonians who travel through time recording historic events as they occur so that they could return to the future and correct the errors in our hall of records.” Da’Quan remembered the conversation. “Jada, no one knows when or where they will show up, they are sworn to secrecy so they don’t pollute the timeline. The Time Travelers are forbidden to interact with anyone outside of their own time. Do you realize the chaos and damage that could be done if just one Time Ship should fall into the wrong hands? Do you understand the ramifications……..

|

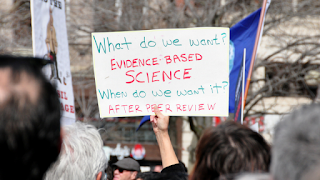

| Image Source: Link below. I realize it doesn't "chant," but you clearly get the meaning and intent. |

Higher priority service moves your order up on the list of our obtainable orders. Even then we are prepared to do number of revisions for you in case you require some last minute alterations to your assignment. In order to make the appropriate choice, I have decided to verify on the internet blogs and reviews for a feedback on this service. I attempted several assignment help solutions but was never satisfies but because I availed solutions from I am entirely satisfied as they do the function as instructed. ALL Sorts OF Professional WRITERS Available TO Provide Very best & Cheap ASSIGNMENT Assist UK OF ANY ACADEMIC LEVEL AT Here! There are a lot of assignment support provider companies that have a group of experienced and specialist writers who do in depth study and come up with the best assignments that are plagiarism free and error-free.

Our on the web assignment support service covers subjects that are tough to grasp, like Microbiology, Biochemistry, Engineering drawing and so on. Sensible writers ask their customer care staff to directly communicate with the students through chat to know a lot more about the assignment requirements. With our effective and swift assignment assist, deadlines will no longer be looming over you. If you are in a confusion that you ought to get assignment support in UK from us or not, then you must appear at the aspect that most of the firms do not offer you any guarantees. As per our experienced professionals, they analyzed that the requirement of students are not constraint in this subject and they require aid with numerous locations. Our aim is to provide quality assignment writing service that can fetch good grades. Our assignment experts operates difficult to reside up to the expectations and provide total peace of mind.

To relieve your stress we recommend you to make use of our on-line assignment aid service to cope up with the stress of assignments while getting some slack time for your self for the duration of your busy schedule. We offer the urgent assignment help from start off to finish, no matter what the type of writing you are assigned by the college or organization.

Finance homework is not a devil, Lets score a high grade in finance assignment: It is unfair to say that Finance is much less well-liked than any other management course. We pride ourselves to deliver exquisitely carried out homework and assignment in the shortest achievable time frame whilst sustaining the high quality in our perform. Each student is worried about the payment procedure which the assignment assist organizations adopt, as they are scared of the frauds and fake assignment helpers, but when you are with you want not have to worry about the payment concerns anymore. The solutions that we prepare are not only for submitting but also aid in gathering information about the assignment topic. EssayCorp has a team of professionals to provide you with an outstanding assignment aid in The USA, UK and Australia. Thus we have developed a platform right here to support out the students in their research.

Specialist academic writers constantly make positive to supply assignment material whose content material is entirely original for on the web assignment help. Our specialists have access to 1000s of database of regular libraries, which are used as references in your assignment. Plagiarism is a serious problem, and you do not want to worry about it when you submit your assignment. As the payments are processed, you can keep assured, as your assignment is already in method. Yes, our rates for your assignment help assist options are inexpensive and never costly. The student advisors operate 24/7, 365 to support you with your assignment or homework.

In case you are struggling with case research assignments, do not hesitate to hire an assignment writing specialist who can do assignment. Our assignment assist authorities have either Masters or Doctorate degrees in their respective subjects from renowned universities and colleges like Harvard, Oxford as nicely as they are providing on the internet aid to students for years.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/ntXmiXdgznY

We obligate to make offered the ideal assignment services, prepared team of proficient essayists. Eduwizards is the location to discover the necessary help, guidance and guidance with student assignments and Eduwizards tutors are ideally suited to provide such assignment aid. Our assignment support solutions are customised and we guarantee you get undivided interest when you contact us. We believe that very good education rears responsible citizens and it is right here that we excel. Now as your greatest assignment buddy, it really is our duty to take it forward and make your assignments really Impactful, Memorable and Persuasive. The assignment carried out by us will certainly prove a key to achievement in your academics.

To score very good marks in such a competitive globe is extremely hard you have to be very excellent with top quality and submit online assignments on time. I was completely satisfied with the assignment.I got assignment back prior to the deadline day and i was extremely content. Fortunately You Are Landed On The Appropriate Location As We Will Offer You Exceptional Assignment Writing Service On-line By means of Experienced Squad... Assured! We can supply aid with any assignment aid USA or homework from grade 5th to college, graduate level or University level. As soon as we evaluate your distinct specifications, we then delegate directions to our team with regards to your specific assignment. In created economies like Australia or US, there are several students who are busy with portion-time jobs and demand on the web assignment support. Our foremost notion is to deliver the on the web assignments help inside the time as we understand that student's profession is based on these assignments.

If you are worrying that if you employ an assignment aid specialist and you will get a number of comments from your professor and less time to revise it, then you need not have to worry any more, as with you will get free revisions till you get happy with your function. There are a lot of web portals and online platforms that supply on-line assignment writing services. The bottle line is…If you want to succeed, then appear out for a reliable assignment service UK. Our service is exclusively for high college, college and university students of Australia. The assignment support services supplied by these guys are excellent that too withinthe greatest inexpensive prices.

For these factors our service has proven by means of the years to be one particular of the most dependable companies that supply homework writing support. You also can optimise your academic overall performance by acquiring assignment help from our professional assignment writer UK. We assure to deliver you custom assignment that could genuinely influence your reviewer to reward you reputable grades. Your cash should not be unnecessarily spent in the name of receiving a top quality assignment. No A lot more Lamenting More than the Tedious Homework When Our Assignment Writing Service Is Here To Support You Out!

To understand far more about our solutions, please go to our Weblog We hold you updated about various assignment solutions and the issues posted by you on our forum. You can get assignment aid in distinct cities across the UK. Our assignment authorities are present in London, Manchester, Birmingham, Ireland and England. Our firm is not there just to earn revenue, but make a difference in student's lives by assisting and contributing to solving their academic assignment difficulties merely. When I necessary assignment help, I have stumbled upon a service referred to as Australian Writings.

We have a team of handpicked writers, prepared to facilitate the finding out method of every single student and offer its trustworthy writing aid with all type of written assignments. Our PHd writers have sufficient skills to offer good quality dissertation support in Australia. Assignments are completed on time and most usually a head of itSo, the students can assessment assignment function keenly ahead of its submission. Providing inquiries or needed data for the Student assignment can help the student to get began.

Now you may be wondering exactly where I’m going with this and I will touch upon two issues that I’m combining. I have noticed the need for positive imagery for young black women and girls, a few forward thinking women have decided to tackle the issue and they have made me very proud. Black Girls Rock, which was founded by Beverly Bond, has been instrumental in putting various individuals in the public eye. Ms. Bond has filled a space at a time when there seems to be concerted attacks upon the esteem of black women not only from outside the community, but some of my very own brothers, that is another issue that I will jump into at another time. Also as I look at the latest controversy online brought to us by the casting of the movie “Ghost In The Shell”, this topic really makes sense. The casting of Scarlett Johansson as the lead protagonist Major Motoko Kusanagi, (who for the movie is simply titled the Major) had caused others to speak out about the pick. The Asian American actresses Ming-Na Wen and Constance Wu were some of the more vocal in opposition to the casting, coincidentally actress and director Joan Chen looked at it as a situation where the filmmaker had the right to cast their movie as they saw fit. Strangely some in Japan had no issues with the pick either because they stated that they had expected someone white to take the role. Sam Yoshiba, director of the international business division at Kodansha's Tokyo headquarters (the company that holds the rights to the series and its characters), had this to say, "Looking at her career so far, I think Scarlett Johansson is well cast. She has the cyberpunk feel. And we never imagined it would be a Japanese actress in the first place... this is a chance for a Japanese property to be seen around the world." Of course the director Rupert Sanders has justified his decision. Johansson has recently given an interview in Marie Claire where she stated that she approached the role with a focus on gender not race. She made a claim of doing it for feminism. Interesting. I would like her to really explain that in detail to we can better understand where she’s coming from. The role is only possible because a Japanese man, Masamune Shirow, created this storyline. From what I can recall “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” did just fine with Michelle Yeoh as the warrior Yu Shu Lien. So does all representation matter or nah?

I do not hope to offend but to create a dialogue, from my vantage point, it seems as if defeat has been accepted with the “Ghost In The Shell” matter from some. Anytime you come out and say that you did not expect one of your own to portray imagery that came from your own, that to me is conceding. I could be wrong. That perception of mine, which I admit could be wrong, is why I feel that imagery of one’s self is all-important.

For myself from historical matters to fictional portrayals, we must make sure that the imagery we project is one that our children as well as fellow adults can relate too on a visual level. The positive reinforcement that you can get from seeing yourself is a tremendous boost to one’s self esteem. Talk with those who saw Nichelle Nichols as Lieutenant Uhura for the first time on screen for clarity, Astronaut Mae Jemison, i.e. The feedback and responses from the movie Hidden Figures is more proof that representation matters. The proof was seen all across social media platforms. As Gabby Douglas and Simone Biles captured the attention of the nation during the 2012 and 2016 Olympics, our young were inspired. As the live broadcast of the Wiz highlighted, representation truly does matter.

Very soon a show that I enjoy despite the reservation of some, Underground, (which airs on WGN by the way), will return to the airwaves. This season they introduce Harriet Tubman, I have no issue with this new mythologizing of her. Just as I see nothing wrong with the new comic book series by David Crownson, “Harriet Tubman Demon Slayer.” Others have taken their historical figures and made them even bigger in life than they already were, why shouldn’t we. The new myth making of Harriet can open the door for others who have not been discovered by the vast populace of black people not only here in the good ole US of A, but globally. From Spartacus to 300, the Tudors, King Arthur: Legend of the Sword, etc, these stories have been given to us repeatedly. Now it’s our turn to give representation for our people. If Milla Jovovich can appear in “The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc”, surely Nicole Beharie, Danai Gurira, Sonequa Martin-Green, Florence Kasumba, Lupita Nyong’o, Kerri Washington, Sana Lathan, Viola Davis, Zoe Saldana, Tessa Thompson, and a few others that I could name who have shown that they can take on roles where action are required could play the people I will name. I could very well see Kerri Washington or Liya Kebede as Queen Yodit/Gudit/Judith who is known for her war against the Axumite Empire. Queen Latifah could pull off Stagecoach Mary Fields, Sonequa Martin-Green or Sana Lathan as Cathay Williams. A whole series could be done on the Kushite Queens and their battles with Rome as well as the Hausa warrior queens. Just as the Game of Thrones has become must watch TV, why not the Rain Queens of South Africa? The possible shoots in South Africa alone would sell that story. If JK Rowling could include the Mountains of the Moon and the Uagadou School of Magic in her Harry Potter universe, we definitely could do the same with creating a unique space. Imagery does matter right? From Africa to America the history is rife with women whose stories could be mythologized. From scholars to warriors, the stories are there for us to tell.

In 2017 we have no reason for our young women in training to have issues with the imagery that they see. What mainstream media won’t provide to fill the vacuum, we should with glee. I have witnessed Beyoncé open the door to those that don’t know or aren’t familiar with Yoruba traditions. That’s a whole another pantheon with images that can be used in the same way that those of the Greeks have been. Out of them we have the iconic Wonder Woman, which has been used as an empowerment tool. Why couldn’t a character based off of Oshun, Yemaya, or Oya serve the same purpose? Especially Oya the warrior goddess, with the climate of these perilous times, one based off of her could serve a much-needed purpose. Coincidentally DC Comics Wonder Woman is linked to Athena who was originally a black goddess.

Fortunately a few have already decided to take matters into their own hands and produce work that can be our very own propaganda that empowers. Where those who brought us all of the various anime images failed, we can succeed. Those individuals may look at my words as being misguided, but the fact that I look at the characters and see blonde haired blue eyed drawings consistently means that I’m right. When I look at the art of anime I’m often confused because from my bird eye’s view the heroes often do not resemble those within the culture that the artwork comes out of. I could be wrong I must say once again. The reasons given as to why the protagonist often favor outsiders to the Japanese culture really do not hold much weight with me, but they like it and I love it. If they want us to believe that Disney is the reason for the look of the various anime characters and that they see them as Japanese, I’m not one to argue with them. There are enough articles littering the web with admonishments and denials on the topic. I’m pretty sure that if anyone from Japan were to see my thoughts they would have a swift reply about my lack of understanding. I’m ready for it. With that being said, although my curiosity has led to my becoming informed on various matters, my concern is about the establishment of representations of our own for years down the line. I want us to get to a point whereas whatever looks of ours graces the screen we are the ones to craft it so that we embrace it, be it from the lightest to the darkest among us, a matter that must be dealt with. However our women chose to wear their hair, another issue of contention that needs to be solved because it has caused another unnecessary divide. Once we’re at a point where we fully embrace us and write our own narrative, those on the outside influence will wane because of the options that we present to counter them. This powerful tool that is the Internet has changed the paradigm considerably. The Grammys that was just broadcast showed us this with Chance the Rapper being awarded on there. The ball is in our hands now, it has been for a while, we’ve just been slow to pick it up and run with it. Anyone that has a desire to embrace the world of art or literature and they’re not sure of what subject matter to tackle, they can go to their search engine and find inspiration. If fiction is the lane that they want to fill, social media can definitely provide source material. A lot of our folks have very vivid imaginations and are missing their callings as becoming our very own James Cameron, George Lucas or Stephen Spielberg. I’m prone to embrace stories told from the historical aspect. The pride that the stories of the past instill can’t be measured at all. As they say when you know better you do better. I very much desire to see a Queen Nzinga on screen; a Dahia Al-Kahina (another historical giant hijacked from our illustrious past) in all her gloriousness, dark skinned with her “mass” of hair (afro or locs perhaps) and big eyes as the Arabs described her in their seventh century writings. I want to see Marie Maynard Daly or Latanya Sweeney…who you say…I just gave your daughters and son’s individuals to do a book report on. Do not just read this, look up some of my talking points and discuss them among yourselves. Pass the word of what you find so that we can plant the seeds for the next wave of possible artist, authors, filmmakers, painters, sculptors, and tastemakers who push our image out to the world. This conversation is just the beginning…

http://carbon-ar.squarespace.com/blog/2017/2/22/all-representation-matters-or-nah

When I was in Nigeria in 1989. My friend and employer Precious Benson told me she wanted to introduce me to this guy, Bolaji Badejo, who said he was the creature in the film E.T. and he was very very tall. She did not know her sci-fi films. I blew it off.

We saw him several times in the market from a distance, because he was really tall and she kept promising to get us together to talk. I am so regretful I did not pudh hr harder so he could tell me the title of the film he was in. Little did I imagine ALIEN was the film he was really in.

Badejo had been diagnosed with sickle cell anaemia when he was a kid. When he was 39, Bolaji got sick and he died December 22, 1992 in St. Stephen Hospital in Ebute Metta, Lagos.

|

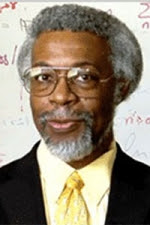

| Distinguished University Professor, Regents Professor & Director |

|

| Science Magazine: Presidential Medal of Freedom Honors a NASA 'computer' |

Call it a Black History Month Twofer. Tomorrow will be a twofer with a slight twist for the month and physics. You'll see what I mean.

|

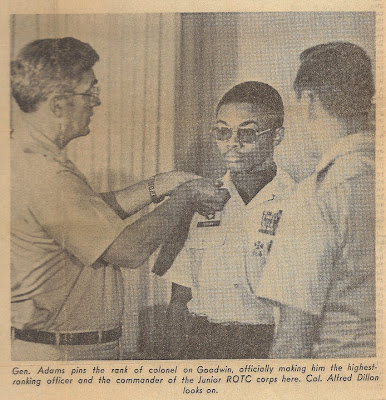

| Robert H. Goodwin is kneeling, lower left. |

|

| Image Source: The (former) Winston-Salem Sentinel |

This is an incredible breakthrough role!

http://www.cinemablend.com/new/Octavia-Spencer-Play-God-Shack-Get-Details-70193.html

Over the years we've seen many actors portray God on the big screen, from George Burns to Morgan Freeman, but now it is apparently Octavia Spencer's time toe become omnipotent and all-powerful. This is because she is now in final negotiations to play God in an adaptation of the novel The Shack, which is now in the works over at Lionsgate.