Credit: Menno Schaefer/Adobe

Starlings flock in a so-called murmuration, a collective behavior of interest in biological physics — one of many subfields that did not always “belong” in physics.

Topics: Applied Physics, Cosmology, Einstein, History, Physics, Research, Science

"To be rather than to seem." Translated from the Latin Esse Quam Videri, which also happens to be the state motto of North Carolina. It is from the treatise on Friendship by the Roman statesman Cicero, a reminder of the beauty and power of being true to oneself. Source: National Library of Medicine: Neurosurgery

If you’ve been in physics long enough, you’ve probably left a colloquium or seminar and thought to yourself, “That talk was interesting, but it wasn’t physics.”

If so, you’re one of many physicists who muse about the boundaries of their field, perhaps with colleagues over lunch. Usually, it’s all in good fun.

But what if the issue comes up when a physics faculty makes decisions about hiring or promoting individuals to build, expand, or even dismantle a research effort? The boundaries of a discipline bear directly on the opportunities departments can offer students. They also influence those students’ evolving identities as physicists, and on how they think about their own professional futures and the future of physics.

So, these debates — over physics and “not physics” — are important. But they are also not new. For more than a century, physicists have been drawing and redrawing the borders around the field, embracing and rejecting subfields along the way.

A key moment for “not physics” occurred in 1899 at the second-ever meeting of the American Physical Society. In his keynote address, the APS president Henry Rowland exhorted his colleagues to “cultivate the idea of the dignity” of physics.

“Much of the intellect of the country is still wasted in the pursuit of so-called practical science which ministers to our physical needs,” he scolded, “[and] not to investigations in the pure ethereal physics which our Society is formed to cultivate.”

Rowland’s elitism was not unique — a fact that first-rate physicists working at industrial laboratories discovered at APS meetings, when no one showed interest in the results of their research on optics, acoustics, and polymer science. It should come as no surprise that, between 1915 and 1930, physicists were among the leading organizers of the Optical Society of America (now Optica), the Acoustical Society of America, and the Society of Rheology.

That acousticians were given a cold shoulder at early APS meetings is particularly odd. At the time, acoustics research was not uncommon in American physics departments. Harvard University, for example, employed five professors who worked extensively in acoustics between 1919 and 1950. World War II motivated the U.S. Navy to sponsor a great deal of acoustics research, and many physics departments responded quickly. In 1948, the University of Texas hired three acousticians as assistant professors of physics. Brown University hired six physicists between 1942 and 1952, creating an acoustics powerhouse that ultimately trained 62 physics doctoral students.

The acoustics landscape at Harvard changed abruptly in 1946, when all teaching and research in the subject moved from the physics department to the newly created department of engineering sciences and applied physics. In the years after, almost all Ph.D. acoustics programs in the country migrated from physics departments to “not physics” departments.

The reason for this was explained by Cornell University professor Robert Fehr at a 1964 conference on acoustics education. Fehr pointed out that engineers like himself exploited the fundamental knowledge of acoustics learned from physicists to alter the environment for specific applications. Consequently, it made sense that research and teaching in acoustics passed from physics to engineering.

It took less than two decades for acoustics to go from being physics to “not physics.” But other fields have gone the opposite direction — a prime example being cosmology.

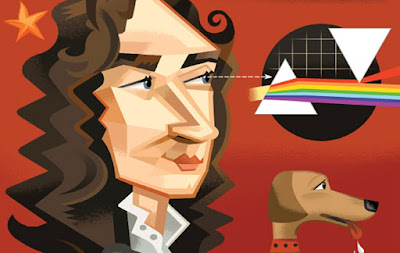

Albert Einstein applied his theory of general relativity to the cosmos in 1917. However, his work generated little interest because there was no empirical data to which it applied. Edwin Hubble’s work on extragalactic nebulae appeared in 1929, but for decades, there was little else to constrain mathematical speculations about the physical nature of the universe. The theoretical physicists Freeman Dyson and Steven Weinberg have both used the phrase “not respectable” to describe how cosmology was seen by physicists around 1960. The subject was simply “not physics.”

This began to change in 1965 with the discovery of thermal microwave radiation throughout the cosmos — empirical evidence of the nearly 20-year-old Big Bang model. Physicists began to engage with cosmology, and the percentage of U.S. physics departments with at least one professor who published in the field rose from 4% in 1964 to 15% in 1980. In the 1980s, physicists led the satellite mission to study the cosmic microwave radiation, and particle physicists — realizing that the hot early universe was an ideal laboratory to test their theories — became part-time cosmologists. Today, it’s hard to find a medium-to-large sized physics department that does not list cosmology as a research specialty.

Opinion: That's Not Physics, Andrew Zangwill, APS