|

| A meme of past memes - seemed apropos. |

Topics: Astrophysics, Humor, Science Fiction, SETI

Note: I use three sources for the commentary I've seen breathlessly displayed on the Internet speculating there may be 36 communicative (but, noticeably silent) civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy. I grinned, and composed the combo meme above. Two words came to mind on my social media feed: click bait.

*****

The number 42 is, in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, the "Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything", calculated by an enormous supercomputer named Deep Thought over a period of 7.5 million years. Unfortunately, no one knows what the question is. Source: Wikipedia

*****

It's been a hundred years since Fermi, an icon of physics, was born (and nearly a half-century since he died). He's best remembered for building a working atomic reactor in a squash court. But in 1950, Fermi made a seemingly innocuous lunchtime remark that has caught and held the attention of every SETI researcher since. (How many luncheon quips have you made with similar consequence?)

The remark came while Fermi was discussing with his mealtime mates the possibility that many sophisticated societies populate the Galaxy. They thought it reasonable to assume that we have a lot of cosmic company. But somewhere between one sentence and the next, Fermi's supple brain realized that if this was true, it implied something profound. If there are really a lot of alien societies, then some of them might have spread out.

Fermi realized that any civilization with a modest amount of rocket technology and an immodest amount of imperial incentive could rapidly colonize the entire Galaxy. Within ten million years, every star system could be brought under the wing of empire. Ten million years may sound long, but in fact it's quite short compared with the age of the Galaxy, which is roughly ten thousand million years. Colonization of the Milky Way should be a quick exercise.

So what Fermi immediately realized was that the aliens have had more than enough time to pepper the Galaxy with their presence. But looking around, he didn't see any clear indication that they're out and about. This prompted Fermi to ask what was (to him) an obvious question: "where is everybody?"

SETI Institute: Fermi Paradox, Seth Shostak, Senior Astronomer

*****

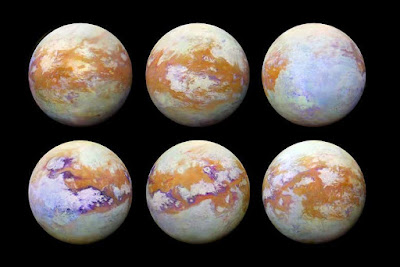

How many intelligent alien civilizations are out there among the hundreds of billions of stars in the spiral arms of the Milky Way? According to a new calculation, the answer is 36.

That number assumes that life on Earth is more or less representative of the way that life evolves anywhere in the universe — on a rocky planet an appropriate distance away from a suitable star, after about 5 billion years. If that assumption is true, humanity may not exactly be alone in the galaxy, but any neighbors are probably too far away to ever meet.

On the other hand, that assumption that life everywhere will evolve on the same timeline as life on Earth is a huge one, said Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, who was not involved in the new study. That means that the seeming precision of the calculations is misleading.

"If you relax those big, big assumptions, those numbers can be anything you want," Shostak told Live Science.

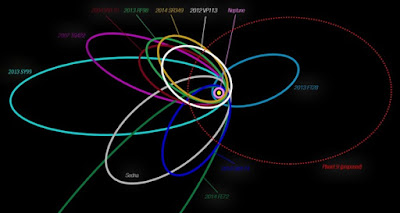

The question of whether humans are alone in the universe is a complete unknown, of course. But in 1961, astronomer Frank Drake introduced a way to think about the odds. Known as the Drake equation, this formulation rounds up the variables that determine whether or not humans are likely to find (or be found by) intelligent extraterrestrials: The average rate of star formation per year in the galaxy, the fraction of those stars with planets, the fraction of those planets that form an ecosystem, and the even smaller fraction that develop life. Next comes the fraction of life-bearing planets that give rise to intelligent life, as opposed to, say, alien algae. That is further divided into the fraction of intelligent extraterrestrial life that develops communication detectable from space (humans fit into this category, as humanity has been communicating with radio waves for about a century).

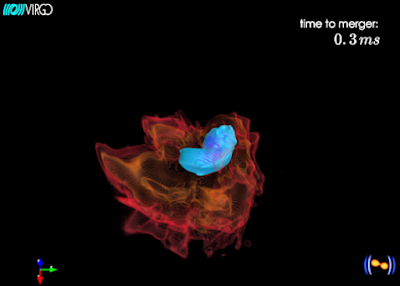

The final variable is the average length of time that communicating alien civilizations last. The Milky Way is about 14 billion years old. If most intelligent, communicating civilizations last, say, a few hundred years at most, the chances that Earthlings will overlap with their communications is measly at best.

Solving the Drake equation isn't possible, because the values of most of the variables are unknown. But University of Nottingham astrophysicist Christopher Conselice and his colleagues were interested in taking a stab at it with new data about star formation and the existence of exoplanets, or planets that circle other stars outside our own solar system. They published their findings June 15 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Are there really 36 alien civilizations out there? Well, maybe. Stephanie Pappas, Live Science