Topics: Bioengineering, Optical Physics, Nanorods, Nanotechnology

Even in the dark, rattlesnakes and their fellow pit vipers can strike accurately at small warm-blooded prey from a meter away. Those snakes, and a few others, can see in the IR—but not with their eyes. Rather, they have a pair of specialized sensory organs, called pit organs, located between their eyes and their nostrils and lined with nerve cells rich in temperature-sensitive proteins that cause the neurons to fire when heated.1 The pits work like pinhole cameras to focus incoming thermal radiation onto their heat-sensitive back walls; the thermal images are then superimposed with visual images in the snake’s brain.

Heat-responsive neurons are not unique to snakes. We have them over every inch of our skin, to feel objects warm to the touch, and on our tongues, to taste spicy food. But the snakes’ ability to resolve the source of radiated heat at a distance is unusual.

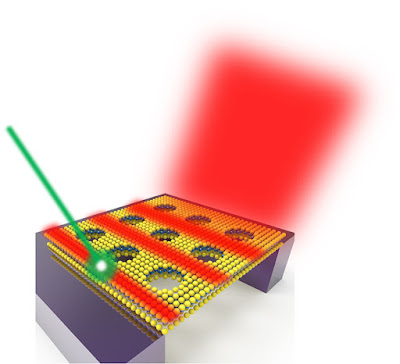

Inspired by the snakes, Dasha Nelidova and her colleagues at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology in Basel, Switzerland, are developing a new treatment for forms of blindness caused by the degeneration of retinal photoreceptors.2 Using gene therapy, they endow remaining retinal cells with thermoresponsive proteins, thereby compensating for their lost light sensitivity with heat sensitivity. The proteins by themselves aren’t sensitive enough to rival normal vision, so the researchers tether them to gold nanorods, as shown in figure 1. The 80-nm-long nanorods strongly absorb near-IR light at 915 nm and convey the concentrated heat to the attached proteins.

Near-IR nanosensors help blind mice see, Johanna L. Miller, Physics Today