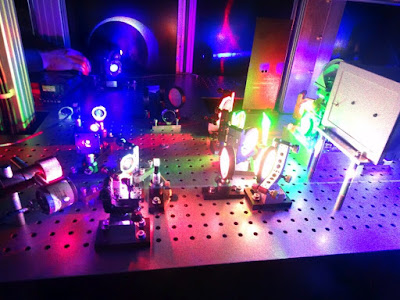

In this image, optical pulses (solitons) can be seen circling through conjoined optical tracks. (Image: Yuan, Bowers, Vahala, et al.) An animated gif is at the original link below.

Topics: Applied Physics, Astronomy, Electrical Engineering, Materials Science, Nanoengineering, Optics

(Nanowerk News) When we last checked in with Caltech's Kerry Vahala three years ago, his lab had recently reported the development of a new optical device called a turnkey frequency microcomb that has applications in digital communications, precision timekeeping, spectroscopy, and even astronomy.

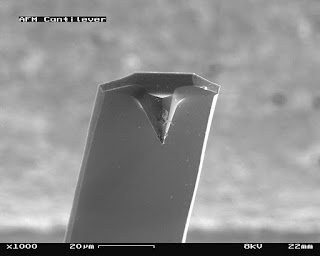

This device, fabricated on a silicon wafer, takes input laser light of one frequency and converts it into an evenly spaced set of many distinct frequencies that form a train of pulses whose length can be as short as 100 femtoseconds (quadrillionths of a second). (The comb in the name comes from the frequencies being spaced like the teeth of a hair comb.)

Now Vahala, Caltech's Ted and Ginger Jenkins, Professor of Information Science and Technology and Applied Physics and executive officer for applied physics and materials science, along with members of his research group and the group of John Bowers at UC Santa Barbara, have made a breakthrough in the way the short pulses form in an important new material called ultra-low-loss silicon nitride (ULL nitride), a compound formed of silicon and nitrogen. The silicon nitride is prepared to be extremely pure and deposited in a thin film.

In principle, short-pulse microcomb devices made from this material would require very low power to operate. Unfortunately, short light pulses (called solitons) cannot be properly generated in this material because of a property called dispersion, which causes light or other electromagnetic waves to travel at different speeds, depending on their frequency. ULL has what is known as normal dispersion, and this prevents waveguides made of ULL nitride from supporting the short pulses necessary for microcomb operation.

In a paper appearing in Nature Photonics ("Soliton pulse pairs at multiple colors in normal dispersion microresonators"), the researchers discuss their development of the new micro comb, which overcomes the inherent optical limitations of ULL nitride by generating pulses in pairs. This is a significant development because ULL nitride is created with the same technology used for manufacturing computer chips. This kind of manufacturing technique means that these microcombs could one day be integrated into a wide variety of handheld devices similar in form to smartphones.

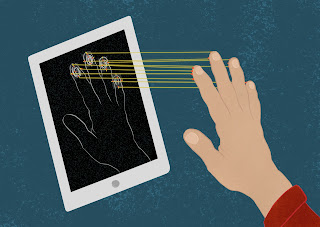

The most distinctive feature of an ordinary microcomb is a small optical loop that looks a bit like a tiny racetrack. During operation, the solitons automatically form and circulate around it.

"However, when this loop is made of ULL nitride, the dispersion destabilizes the soliton pulses," says co-author Zhiquan Yuan (MS '21), a graduate student in applied physics.

Imagine the loop as a racetrack with cars. If some cars travel faster and some travel slower, then they will spread out as they circle the track instead of staying as a tight pack. Similarly, the normal dispersion of ULL means light pulses spread out in the microcomb waveguides, and the microcomb ceases to work.

The solution devised by the team was to create multiple racetracks, pairing them up so they look a bit like a figure eight. In the middle of that '8,' the two tracks run parallel to each other with only a tiny gap between them.

Conjoined 'racetracks' make new optical devices possible, Nanowerk.