|

| Image Source: Scientific American, Antiscience Beliefs Jeopardize U.S. Democracy, Shaun Lawrence Otto, October 16, 2012, see "trinity of three greatest men" link below. |

Topics: Commentary, Science, SETI, STEM, Research

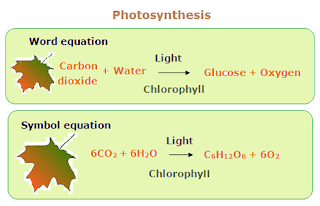

Science: 1 a : an area of knowledge that is an object of study b : something (as a sport or technique) that may be studied or learned like a science c : any of the natural sciences (as biology, physics, or chemistry) Middle English science "the state of knowing, knowledge," from early French science (same meaning), from Latin scientia (same meaning)

Recently, there's been buzz on the Internet about a so-called mega structure (i.e. a Dyson Sphere) seen 1,500 light years away around its star. Related somewhat, astrophysicist Sara Seager thinks she can detect life on exoplanets by examining the spectrum of sodium (see BBC link below).

The quintessential question is - for any science discipline, from astronomy, biology, climate science and physics: how do scientists "know"?

They know first by sheer practice and enthusiasm. Everyone in STEM can recount the very instance that made such an impression on them that they decided to pursue a path to search the unknown - that labeled them "nerd"; weird and steeled their resolves against the tide of conformity. They studied all subjects with equal vigor, but particularly the science subjects. It formed a culture and a value system. Nerd went from epithet to web sites, social media forums; blerds, blogs and t-shirts. They know by observation, forming hypothesis, doing experiments; rigorously defending and refuting positions...it sounds a lot like democracy, or at least how Thomas Jefferson envisioned it on the foundation of his "trinity of three greatest men." If knowing knowledge is thesis, then it's antithesis is prideful, unknowing ignorance.

Scientists and engineers will know knowledge, test it, debate it; refute it. They will confirm an ancient civilization that existed in our past...or, not. They have consensus on climate change, not conspiracy. I'm sure they would rather be wrong. They have a vested interest beyond an elaborate Ponzi scheme: their families. Some legacies have far more value than money.

Pseudoscience differs from erroneous science. Science thrives on errors, cutting away one by one. False conclusions are drawn all the time, but they are drawn tentatively. Hypotheses are framed so they are capable of being disproved. A succession of alternative hypotheses is confronted by experiment and observation. Science gropes and staggers toward improved understanding. Proprietary feelings are of course offended when a scientific hypothesis is disproved, but such disproofs are recognized as central to the scientific enterprise.

Pseudoscience is just the opposite. Hypotheses are often framed precisely so they are invulnerable to any experiment that offers a prospect of disproof, so even in principle they cannot be invalidated. Practitioners are defensive and wary. Skeptical scrutiny is opposed. When the pseudoscientific hypothesis fails to catch fire with scientists, conspiracies to suppress it are deduced.

“I would rather have questions I can’t answer, than answers I can’t question.” Richard Feynman

BBC Future: If alien life exists on exoplanets, how would we know?

Mouser Electronics: The Truth Is Still Out There. And We’re Still Looking, Barry Manz